Neuropsychological and biological methods are able to objectively capture “moment-to-moment” changes in motivational states. They do so in a way that is almost impossible to assess without otherwise interrupting the participant’s engagement in a task. There are many ways to assess people’s neuropsychological and biological motivational processes, such as the following:

Neuroscience (to measure brain functioning)

- fMRI (functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging). fMRI is used to assess the blood oxygenation level dependent (BOLD) signal as participants engage in a task.

- Electroencephalography (EEG). EEG is used to assess event-related potentials (ERPs) in response to a specific event (e.g., a motivational or emotional episode).

- Electromyography (EMG). Similar to EEG, except one measures electrical activity of muscles (e.g., facial expressions) rather than the brain per se.

- Functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (fNIRS). The assessment of brain activity using a portable and low-cost equipment.

Hormones (to measure stress and endocrine system activity—typically by taking a salivary measure)

- Cortisol

- Oxytocin

- Testosterone

- Immunoglobin-Secretory A

Psychophysiology

- Heart rate (cardiac output, to measure effort)

- Heart rate variability

- Pupil behavior (e.g., gaze and pupil diameter via eye tracking goggles)

- Electrodermal activity

Other Biological Markers of Motivational States

- Glucose

- Voice tone

- Accelerometer

Theoretical contributions of neuropsychological and biological methods

Using the neuropsychological and biological measures, well-known SDT propositions have been re-examined. For example, a handful of neuroscience studies have tested whether extrinsic rewards undermine the beneficial effects of intrinsic motivation. In addition, there have been neuroscience studies testing whether high levels of intrinsic motivation buffered negative effects of difficulties and failures during task performance. In this way, a number of SDT propositions have been confirmed not only by behavioral evidence but also by neuropsychological and biological evidence.

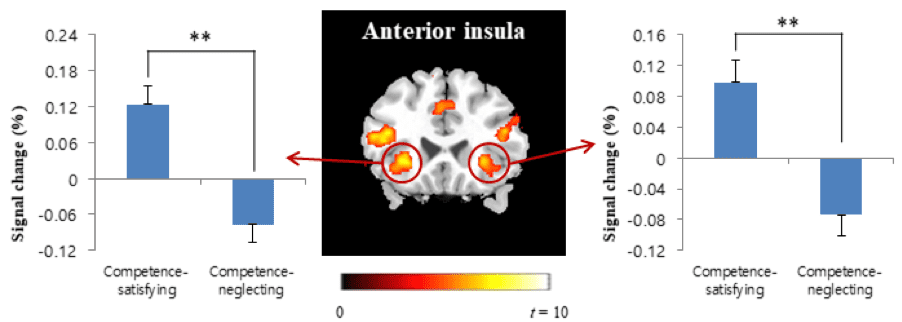

Neuropsychological and biological research contributes not only to the confirmation of SDT but also to the theoretical advances of SDT. For example, SDT postulates that intrinsic motivation is qualitatively different from extrinsic motivation. Neuropsychological and biological findings suggest that the experience of intrinsic motivation is more associated with the neural system of self-processing (e.g., neural activities of anterior insula and anterior cingulate cortex) than is the experience of extrinsic motivation. This finding confirms the unique nature of intrinsic motivation and offers new insight into what the unique nature of intrinsic motivation is.

Two Examples

Neuroscience of Intrinsic Motivation (Lee & Reeve, 2017)

Using fMRI, participants were given optimally challenging tasks to solve while they lay in a scanner and an MRI machine recorded their brain behavior. When participants experienced intrinsic motivation from an optimally challenging task, they showed greater anterior insula activity, striatum activity, and their functional interactions. These neural findings suggest that self-processing and reward processing play crucial roles in the neural system of intrinsic motivation.

Voice Tone while Motivating Others (Zougkou, Weinstein, & Paulmann, 2017)

Using ERP, participants listened to autonomy-supportive messages and voice tones or controlling (pressuring) messages and voice tones. When participants heard controlling messages, late potential ERP amplitudes were enhanced. This suggests that the qualities of messages (particularly controlling messages) are processed rapidly.